The Brothers Lynch explain how they created the sinister atmospheric world for their new sci-fi short

In a post-apocalyptic world where humankind has emerged victorious in a war against artificial intelligent machines, a young girl dares to venture into the unknown. This is Zero, the new sci-fi short film from acclaimed British writer-director duo The Brothers Lynch which has premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Zero, which stars Bella Ramsey (Game of Thrones) and Nigel O’Neill (Bad Day for the Cut), is designed as a standalone story but also as a teaser to a feature length version which Keith and David Lynch are currently developing.

“The concept for the feature version of Zero was born out of wanting to write a coming of age Western, like Slow West and True Grit, but give it a sci-fi edge,” explains David, who shares creative duties with his brother. “As we began to think about our lead character, Alice, we realised that her relationship with her father could reflect the overall idea of intelligent robots rebelling ‘against their creators.”

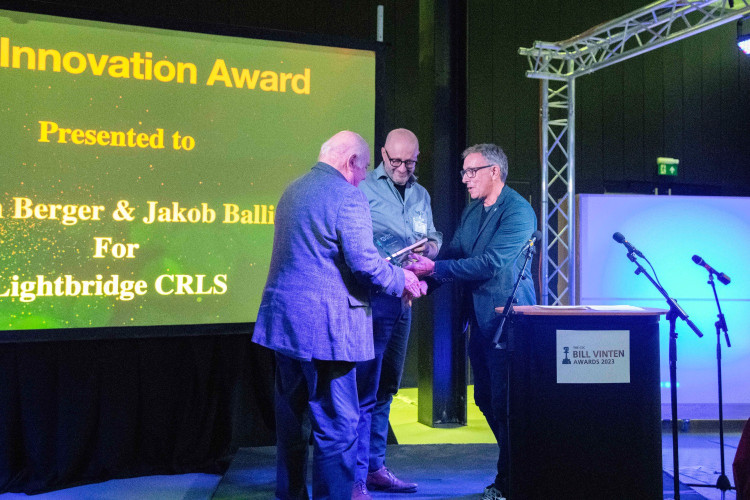

The filmmakers are gathering a growing reputation for original action and suspense drama. Selected as Screen International Stars of Tomorrow and among the top 100 new writers in Hollywood by Tracking Board's Young and Hungry List, the brothers’ thriller TV series, Mother, is being produced by Hook Pictures and Endgame Entertainment and action thriller feature, Final Score, which they wrote, was released in 2018 directed by Scott Mann (Heist), starring Dave Bautista (Guardians of the Galaxy) and Pierce Brosnan (Goldeneye).

For Zero, the brothers found the main location in their home town of Burnham-on-Crouch in Essex. The task for production designer Jason Synnott was to render the beautifully decrepit old house as both haven and prison for the characters.

“I was very keen to see what the Ursa Mini we shot with could do and push it to its limits, as it was a format that I hadn’t worked with previously,” explains cinematographer Adam Etherington (Gwen, Poldark). Working and moving sliders and dollies within the location proved prohibitive as the property was very fragile. The tight three-day shooting schedule also influenced a decision to make use of the lightweight capabilities of the camera.

“We decided that once the Electromagnetic Pulse was about to hit, that would be a good opportunity to develop from solid camera mountings into a more handheld approach,” says Etherington. “We wanted to be able to move easily with Alice throughout the house as she goes about her daily existence, which a handheld approach enabled us to do.”

They primarily worked off of a small package of 2.5k and 4k daylight HMI sources based around the exterior of the location. This was partly a creative choice, and also designed to play to the strengths of the camera’s sensor, based upon what they’d learned through testing.

“It was important to give the directors a freedom to move the camera within the location without a great deal of re-lighting,” says Etherington. “Our budget was very limited, and didn’t allow us the luxury of large sources on machines that we could bounce or play from a distance to provide an even but powerful falloff. So, we diffused the exterior of the windows and played the sources direct.”

This created a strong directional (but soft) light and allowed the character’s freedom to move, while enhancing the sense of claustrophobia by eliminating the outside world from view. The one exception to this is a moment when Alice looks outside whilst investigating a noise.

“We wanted the only time she sees the outside world to be directly connected with an external threat, in order to further enhance her vulnerability and feelings of entrapment.”

They discussed using anamorphics but felt that the authentic feel of a spherical lens would be more in keeping with the desire for the audience to feel close to the lead character. In addition, they would be able to shoot at a faster aperture on spherical lenses which, in turn, allowed more opportunity to focus on the storytelling.

“In selecting the MK2 Zeiss Superspeeds (comprising an 18mm, 25mm, 35mm, 50mm, 65mm, 85mm, all T1.3) we tested a few different lens sets, but felt that the cool hue and defined contrast rendition would accentuate the atmosphere we were looking for,” says Etherington.

For the almost monochromatic feel of Alice’s environment, Synnott and costume designer Lindsey Archer created a world primarily comprised of a tertiary palette of greens and browns.

This absence of deep colour was carried through into post at Molinaire, where senior colourist Chris Rogers was able to enhance the look.

“Chris is a brilliant colourist, and was great in helping us get the most out of the format,” says Etherington. “We’d tested footage from the Ursa Mini Pro in the suite before shooting to see how the best results could be gained. We shared our references and mood boards with Chris, which he then took onboard in finishing the film.”

Perhaps the most arresting visual in the film is a sudden reveal of the epic landscape outside the building where Alice has been living. It’s a wide shot of her walking into marshland dominated by the remains of a giant humanoid robot, its massive fingers poking out of the ground.

The reference for this included the work of artist Simon Stålenhag whose retro-future compositions of giant fallen robots are often situated in landscapes with people dwarfed in the foreground.

Director Gareth Edward’s remarkable creature effects made on a low budget for Monsters was inspiration too.

“It would have been a much easier to create had we had her walk into the marshland with these massive robot shots in the distance haze,” explains Keith, whose background is in motion graphics. “Jason came up with the design for the robot well before shooting began and he suggested a physical build of the robot’s fingers that Alice could walk through. Even though it was outside our budget to fabricate them to that size we became obsessed with the idea. We used the Ursa Mini to shoot tracking tests on the marshes and I started building in Cinema 4D.

We made it even harder for ourselves with a drone shot that pulls around the front of the robot. That said, the biggest challenge wasn’t the robot but compositing plates of real blades of grass blowing in the wind with CG grass.”

Editor Gareth C. Scales, who edited the Lynch’s previous short film Trial, co-edited Zero with Chris Watson. Regular collaborator Carly Paradis provided the score. Ed Barratt of Hook Pictures executive produced with Richard Wylie and Maria Caruana Galizia producing. It is funded by Gunpowder & Sky as part of its Dust sci-fi channel on YouTube.

The ending of Zero is deliberately open to point to a wider narrative to be explored.

“Zero is the first act if you like and the feature will expand on the same characters and story,” says David. “We’ll go into more depth about the psychologically abusive relationship the father has with his daughter – that he is trying to protect her but only succeeds in creating a prison. The feature version is still in early development but we’re excited to dive in.”

Watch Zero online on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mM2ExtmcZ_8&feature=youtu.be