by Dick Hobbs

Issue 80 - August 2013 I was at a conference about workflows the other day. One of the presentations was by a very nice man called Eric Minoli, who is chief engineer at TFO, the French-language public broadcaster in the Canadian province of Ontario.

He illustrated his presentation with a great story. Some friends were invited around to his house for Sunday lunch, and they were chatting with him in the kitchen while he prepared the joint of beef for roasting. They wondered why, before putting it into the oven, he carefully sliced the ends off the joint.

I have always done it, Eric explained. Yes, but why, his friends persisted. Because my mother did it, he added.

He rang his mother, and asked why she always sliced the end off the joint before putting it in the oven. She did not know why: she did it because her mother had always done it.

So Eric rang his grandmother and asked her why she always sliced the ends off the joint before roasting it, a practice which had been passed down through the family. Oh, that was because the oven was not big enough, she said.

The point of the story is that it is all too tempting to do something the way we have always done it, without ever thinking about the reasoning behind it. Given that we are all involved in a huge shift in technology from tapes to files this might be a good moment to at least start asking questions about the way we have always done things.

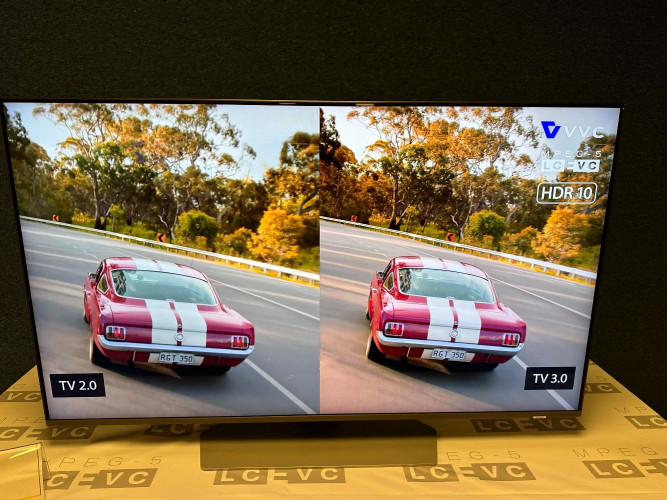

One of the direct points Eric Minoli made in his presentation was that we should stop thinking TV first. Broadcast television, as we used to know it, is now just one output of many. Just because a broadcast server is more expensive than an IT server, does that make it more important?

On one level I disagree with Eric on this one. I think because of the conditioning we have all received as consumers not as experts we do have very high expectations of broadcast television. We really do assume that we are going to get a new picture every 40 milliseconds, and we get cross if we miss even one of them.

We build playout centres to at least five nines reliability 99.999% up time and if broadcast quality means anything today, it certainly means no freezes or spinning wheels. We may get grumpy about less than perfect, seamless content online, but we are more likely to accept it because we remember when internet video was really, really bad. On another level, though, I think he has a point. Broadcasters are now expected to deliver to a lot of different platforms, with each brand of phone or tablet having a different combination of screen size, codec, wrapper, metadata and streaming structure. Why would you not regard the SD and HD broadcast versions as just yet more packages to be processed and spat out of the content factory?

If I may answer my own question, it could be because broadcasters hate the F word. They do not like the concept of their treasured content being pushed through a factory. But that is exactly what a modern facility is, a just-in-time supply chain ensuring each piece of media is in the right place, in the right format, at the right moment.

To get to this supply chain approach, though, we have to change something fundamental we do because we have always done it that way. We regard getting content from ingest to delivery as a technology process, because it was always controlled by the technology.

When VT operators were replaced by robots in Sony LMS or Panasonic Marc (the two competing robot tape libraries when playout automation first started), it did not change the way playout was organised. And when the first Profile servers appeared in playout areas, again the workflow and the operation was precisely the same.

I do not think anyone will argue when I say that, to meet the needs of multi-platform delivery, we have to have largely automated systems. The big leap in logic and in faith is to turn the thinking upside down and define workflows in terms of business requirements not in what the technology can do.

Frankly, the technology can do anything. I know that vendors hate people saying this, but most of it is only software. What will make the difference is how we organise the technology.

In a blissfully ideal world we would set up a set of rules along the lines of have a look at the rights management database, see what we can do with this programme, then do it. If we also asked the system to tell us what resources were used to achieve each output then we would know how much it cost, and we could make real commercial decisions on the viability of providing all these services.

That would be a big change in thinking, but without it we are not taking full advantage of the technological revolution we are undergoing. In simple terms, we now have a much bigger oven: how much longer are we going to slice the ends off the joint?

Dick Hobbs roasts television rare

Author: Dick Hobbs.

Published 1st September 2013