While the original idea for MADI was to cater to a very narrow recording studio application, the standard remains a viable go-to multichannel audio technology. Beginning as a standard in 1991, MADI was first introduced to the world as digital production was beginning to come of age. MADI was put together in 1988 by Solid State Logic, AMS-Neve, Sony (DASH) and Mitsubishi (ProDigi) as a way to transport up to 56 channels of digital audio between large-format audio consoles of the day and digital multi-channel tape machines via 75-Ohm coaxial cables. Both tape-based machines have long since disappeared from the equipment landscape.

MADI attained standard status when adopted by the AES as an open standard for audio exchange in 1991 with revisions in 2003 (AES10-2003) and 2008 (AES10-2008). The AES10-2003 spec mandated connectors to include BNC connectors with coaxial cables (for a 50 meter/164 foot run) and ST1 connectors for fiber-optic installations with a range of up to two kilometers or 1.24 miles. Early on, the format migrated over to the broadcast side as a reliable and easy-to-install method of routing audio throughout a facility. What was started over 20 years ago is experiencing a modern-day renaissance with more and more facilities incorporating the standard.

While MADI retreated through the late-1990s to mid-2000s, the standard became cutting-edge again with a clear industry-wide MADI mandate brought on by the dramatic paradigm shift from tape-based to non-linear, computer-based audio production. The fundamental shift in the industry that replaced copper wire snakes to coax and fiber optics demanded an efficient way to route audio to and from anywhere within a facility. From a systems integration point of view, having one facility-wide routing solution was easier to install and maintain, and MADI, as an existing open standard that owns a reliable track record, was a good choice.

Today, MADI is primarily used in the distribution of audio-only signals within the production environment and has found a particular niche in the OB truck market where weight, simplicity, and reliability are paramount. The U.S. OB market in particular has embraced MADI mainly because of the difference in how people use “comms.” Traditionally, every position would have had an audio monitor being fed with eight channels of analog or AES. Running eight lots of analog audio to every single position through huge patch bays is very cumbersome - very heavy on the copper. When MADI was introduced, rather than using eight lots of analog cables, a single coax cable was used to carry those 64 channels, which can be daisy-chained, with eight groups of eight to the different positions.

The adoption of Dolby ATMOS is also helping to keep MADI relevant in production applications. When creating theatrical releases with ATMOS, MADI is the dominant method for transporting audio. Many live sports productions, typically those delivered in UHD-1 are now accompanied by an ATMOS mix, with MADI still proving its worth, especially in OB trucks. With the potential to support up to 128 objects, ATMOS workflows can be suitably served using one or two MADI streams, allowing for simplified audio infrastructures. Enjoying long-term status, MADI products are readily available from many broadcast and professional audio manufacturers with widespread global adoption.

It goes without saying that the move to IP can’t be ignored and that ‘one size fits all’ tools no longer provide the versatility customers require. More than ever before, those involved in television production and distribution need solutions where functionality can adapt and grow over time, whilst maintaining a user-friendly experience, regardless of the advances in underlying technology. In working with several major greenfield sites and POCs based on ST-2110 it seems that are as many questions being raised around IP as there are being answered. Whilst the shift in infrastructure is becoming more and more a reality, not all customers have the luxury, or desire, to make an immediate change. With production requirements becoming ever more challenging, making the right investment in equipment and technology is not getting any easier. Many broadcasters are concerned about network security and the prospect of their operations being hacked. Unlike an audio over IP network, MADI requires no IP infrastructure and for many customers, MADI provides a familiar, quick to set up, cost-effective solution that requires no new training or investment in IP infrastructure. For such customers, MADI can prove to be the most practical audio standard for events, fly-aways and temporary installs.

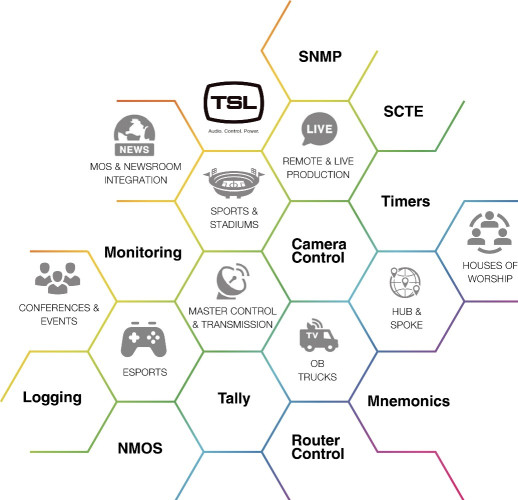

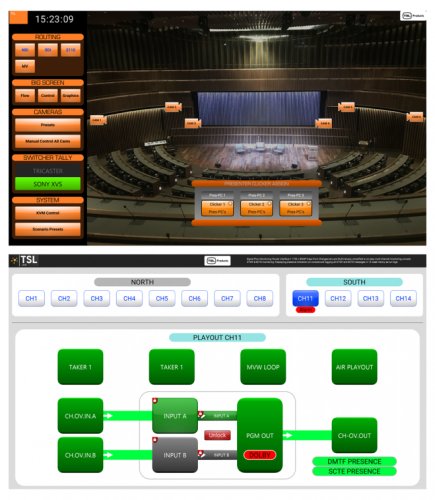

This drive to address our customers’ need for agility and flexibility continues to feed into TSL’s new audio monitoring platform, the SAM-Q. SAM-Q customers can both personalise and protect their SAM-Q products according to their location, application or indeed their own personal preference. With the addition of the SAM-Q MADI license, the ability to support MADI workflows of up to 128 channels without having to use extra hardware that SDI and MADI sources can be monitored simultaneously, from a single position, with the user able to create custom monitoring mixes comprising both MADI and SDI embedded audio sources.

Whilst it is vital to keep an ear to the ground in terms of being active members of leading industry organizations, we must continue to listen to customer feedback and their changing needs, to make sure that the solutions delivered stay at the forefront of evolving workflows. Those of us on the manufacturing side must continue to design products and solutions that support IP infrastructures and embrace emerging technologies, whilst also offering the support for existing and proven standards to future-proof our customer’s investments for years to come.