Here’s an important fact that might get lost in all the noise of the moment. HBO’s Game of Thrones, which is relentlessly covered in the press as well as being talked about by its fans, is not actually terribly popular. The opener of the current (and last, thank goodness) series attracted a consolidated audience of about 3.5 million – that includes 2.7 million who watched the first showing at 2am, plus those who watched it at a more civilised hour, or who recorded it. Informed comment seems to be that those who watch on catch-up at some time in the following week or so might add a million more.

To put that into context, when Nadiya Hussain won Great British Bake Off – without benefit of dragons and certainly with no nudity – the audience reached 14.5 million. In the UK, then, four times as many people watch nice people make cakes in a marquee than watch this sorcery nonsense.

You have probably worked out that I am in the delta 11 million. I tried watching Game of Thrones once, but after 10 minutes I could feel my brain cells dissolving.

If it is a minority interest programme, then, why am I taking up space in this magazine to mention it? First, its production costs are probably a record high for television, much of it spent in its production base in Belfast.

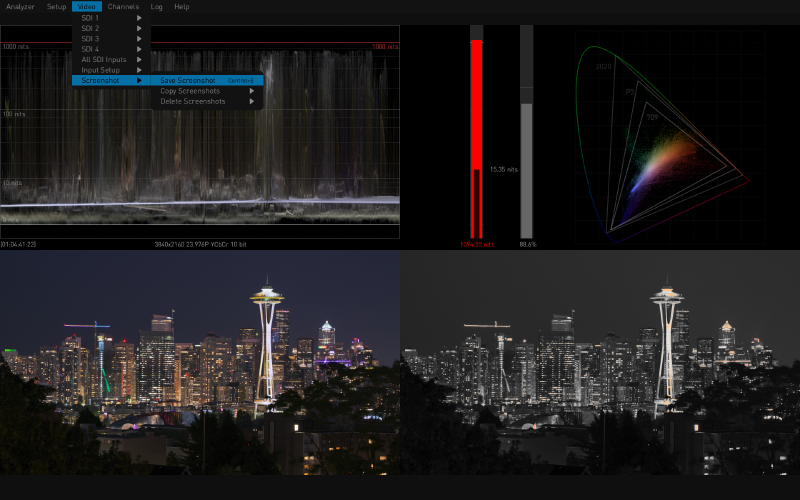

And yet, in the aftermath of the most recent episode – which contained the longest battle scene ever shown, for reasons which I am sure make sense to some – there is a lot of dark (literally) muttering about what you can actually see. A television reviewer described it as a “ponderous, murky mess”, while a highly respected international commentator in television technology said it was the most convincing argument in favour of HDR, because it might have let him see some of the details. Was it “the fog of war”, or was it that your special effects don’t need to be that great if you cannot really see them?

The second reason I wanted to look at Game of Thrones was because of the way it collects hype. There is an enormous amount of talk about a show which does not attract many viewers.

The first episode of this final series was leaked, by DirecTV. Amazon Prime in Germany released episode two early. As Oscar Wilde nearly said, to lose one episode “may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness”.

I find it very hard to believe that the leading satellite broadcaster in the USA can be careless. As part of AWS, the cloud business that is sufficiently secure for the US Secret Service to trust it, I doubt if Amazon Prime is that careless, either.

So are these leaks cleverly managed publicity, aiming to keep the noise levels up? Or am I simply being cynical?

All of which is a roundabout way to start talking about what I saw at NAB, by talking about what I did not see. It was really hard to find anyone who wanted to talk about content security, which I found surprising.

What used to happen was that master tapes were treated with perfect respect, and housed in libraries managed by fierce women who would never let them out again. However much you pleaded that you had to transmit the programme in three minutes’ time.

Another physical layer to the security protocol was that there was not much benefit in anyone intercepting a reel of 1” tape, because no-one apart from broadcasters possessed either VTRs or the skilled engineers required to keep them lined up.

Once content is digital, then copying it, viewing it and processing it is easy. One of the top NAB announcements was DaVinci Resolve 16 from Blackmagic Design. It has excellent editorial and grading facilities, visual effects and motion graphics, and sophisticated audio post, at resolutions up to 8k, and it is free. If you really insist, you can pay £239 and get all that plus multi-user collaboration and HDR. Maybe Game of Thrones didn’t pay the £239.

But the point is that, if you can hack your way in to a digital file, then anyone with a laptop can watch, repackage and deliver that content. So data security is a really big issue – one leak and the intellectual property is anybody’s.

I spoke to Jason Coari of Quantum while in Las Vegas. His view was that you should be able to keep your own machine room safe. “The cloud, too, is inherently safe,” he explained, “but it could be intercepted to and from”. That still seems to be a major concern for content owners.

I also spoke to Savid Sallak of Pixit Media, who is also big on content security. He developed the theme of keeping your machine room safe, by pointing out that you probably have content belonging to several different people in it. If you are a post house, you will be working on multiple projects simultaneously.

So you need something that will provide multi-tenancy security: not only keeping stuff from getting outside the trusted network, but ensuring that each client only sees their own stuff. Again, that is a big concern.

Those who love Game of Thrones are probably also fans of Marvel comic book movies. They certainly make a lot of money: the estimated $400 million budget of Endgame was balanced by $1.25 billion in global box office takings over its opening weekend.

If your post house aspires to work on the Marvel Cinematic Universe (yes, they do call it that), then you have to build a completely separate storage stack which can only be used for Marvel data. No amount of sophisticated multi-tenancy security will get you past that requirement by the production company.

Extreme cases apart, there are now industry bodies proposing the highest standards in content security. This, of course, adds to the alphabet soup of initialisms (they’re only acronyms if you pronounce them as words) we all have to carry around.

TPN is the Trusted Partner Network, a joint venture between MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America, the studios body) and CDSA (Content Delivery & Security Association). It aims to establish a benchmark for security and thence a global directory of trusted partner vendors. According to its website, it “seeks to raise security awareness, preparedness and capabilities within our industry”.

Lewis Kirkaldie of Cinegy – always a reliable source – introduced me to SRT, the Secure Reliable Transport Alliance. This is an open source video transport protocol that optimises streaming performance across unpredictable networks, “bringing the best quality live video over the worst networks”, it says. It does all this while maintaining end-to-end 128 or 256 bit AES encryption.

The initiative came from Haivision and Wowza, but they have made the technology open source and encourage other vendors to join the alliance for a modest fee. Which is how it should be.

Is this obsession with content security really all that important? Well yes, I am afraid it is. Take the case of BeoutQ, a relatively new streaming service from Saudi Arabia which has a remarkable range of content, particularly top sports.

It has this content because, it is alleged, it pirates it from broadcasters with legal rights in the content*.

The situation appears to have arisen outside the world of sport and media, but in geopolitics. Saudi Arabia has fallen out with its neighbour Qatar, by suggesting it supports terrorism. Qatar is the home of leading international broadcasters, including sports broadcaster BeIn. BeIn is not the most popular of broadcasters in the region, being accused of using sovereign wealth funds to drive up the cost of sports rights, but that is not the issue here.

Having imposed a commercial boycott on Qatar, Saudi audiences were faced with missing out on sports action. It was at this point that BeoutQ emerged, often simply pirating the BeIn feed including commentary and replacing the logo bug.

This has turned into an international war of words. “BeoutQ has illegally transmitted BeIn’s coverage of numerous NBA games, US Open Tennis Championships, and many other high-profile sporting events,” the NAB and USTA wrote in a joint submission to the United States Trade Representative.

Sky Sports has made a similar complaint, alleging that it offered direct, unauthorised access to some of Sky’s premium television channels and noting “a wholly parasitic rebranding” of BeIn.

All in all, a very uncomfortable situation, where broadcasters who have spent a lot of money on sports coverage are not receiving the return that their investment deserves. So yes, making sure your signal is hard to hack is a very good plan.

To finish on a cheerier note, though, my favourite comment from NAB this year said all there is to be said about Ultra HD as a commodity. “We needed an 8k screen for demonstrations at NAB,” said Cinegy’s Lewis Kirkaldie. “So we went to Best Buy and bought a television.”